What Would I Change: photographer Jeremy Liebman

In the latest of our series of articles that asks creatives what they would like to change about their industry, editorial and commercial photographer Jeremy Liebman looks to what he can do as an individual

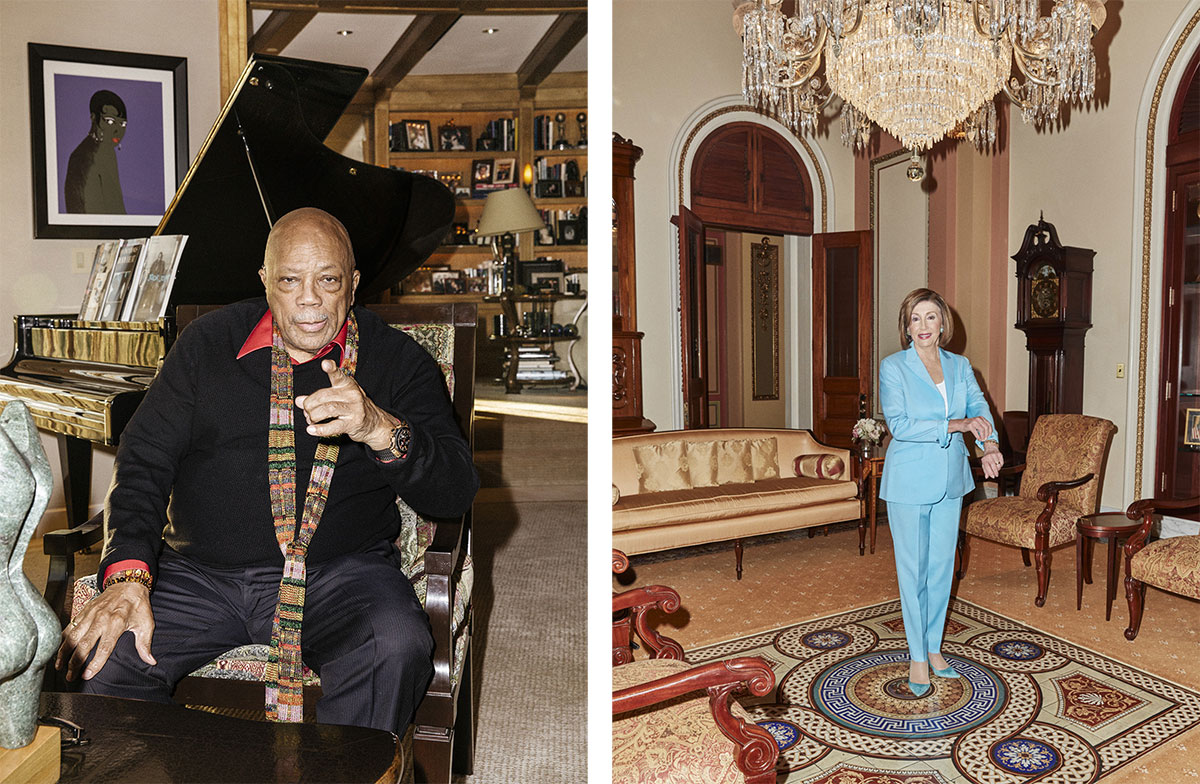

Brooklyn-based photographer Jeremy Liebman is the kind of photographer who flits easily between meaty editorial projects for magazines such as Appartamento, New York magazine, Vanity Fair and the New Yorker, and can also tackle big commercial briefs for the likes of Apple, Nike, Prada, BMW and Wedgwood. His style is punchy and full of contrasts, and he has the ability to convey and capture the real personality of any subject.

When the pandemic hit, advertisers paused upcoming shoots and editorial budgets hung in the balance, meaning Liebman suddenly had no commissions coming in. Rather than dwell on what can’t be controlled, Liebman embraced the opportunity to work on some personal projects as well as a lockdown-led video collaboration started by KesselsKramer.

With this extra time, the photographer also found time to reflect on his place in the industry and how, even as someone who works freelance, he could take on more responsibility for others. For Liebman this starts with the stories he’s telling, and ensuring the publishers and brands he’s working with are also acknowledging their responsibility.

Here, he discusses what shoots are looking like right now in a time of social distancing, the role the creative industry has in dismantling inequality and why he feels like true collaboration might be the way we can move forward.

A time for different opportunities Lockdown has been incredibly strange for me, as I know it has been for all of us. For a few weeks at the end of March and beginning of April, we heard ambulance sirens almost constantly, the hospitals in New York were reaching capacity, and there was still so much about the virus that was unknown, so it was a real time of uncertainty. But it was also an opportunity to pause and reflect on a lot of larger issues.

In terms of work, I had a big ad job scheduled for late March that had to cancel and new commissions went pretty quiet for about three months. In that time, I contributed to a great video project along with several other directors that KesselsKramer did with Efthimis Filippou, the screenwriter of The Lobster and Dogtooth. I also did a personal still life project and worked on some book layouts for a couple of personal photo books.

The changing nature of shoots I just did my first advertising shoot last week with a remote client and ad agency. We had talent, wardrobe, hair and makeup, and props, but we were in a very large studio, so we were able to stay distanced.

Our producer took everyone’s temperature when they arrived, everyone wore masks, and we had disinfectant wipes handy. I worked with an incredible digital tech who set up a remote camera feed to show a wide shot of the studio and shared the capture screen to a Zoom conference call with about 20 people in it, all over the country. We were able to have enough monitors for myself, the prop and wardrobe stylists, and hair and makeup to ensure we could keep six feet of distance. I hope we don’t have to continue this way forever, but it’s good to know that shoots can go on in some capacity for now.

Remote working challenges With remote shooting, either the photographer is remote from the subject (a person, a handbag, a landscape etc), or the photographer is with the subject, but the client is remote. My approach to portraiture relies on interaction and exploration, and a certain level of image quality, which I don’t think remote shooting can capture.

It’s the equivalent of a video call with your friend, rather than being together. I think there are definitely photographers who are more conceptual who do great with remote shooting, my friend Matt Grubb for example, but it just doesn’t work for me. In terms of a normal shoot with remote client input, I come from an editorial background, so smaller shoots are always preferable for me.

The world needs to be celebrated in all of its idiosyncrasies and complexity, rather than narrowly aspirational lifestyle branding

Taking on responsibility as a creative I’ve reflected more on my place in the industry, rather than on the industry itself, particularly in my role in telling stories and being involved in promoting what I think is important. The pandemic has really brought to light a lot of social injustice, particularly in the US, in terms of who is most vulnerable and what protections are in place for them.

I don’t see myself becoming a photo-journalist, but I do want to be sure I’m doing work I believe in. I’ve always aimed for my portraits to celebrate artists and outsiders and for my personal and still life work to challenge the dominant views about craft, taste, and aesthetics. The world needs to be celebrated in all of its idiosyncrasies and complexity, rather than narrowly aspirational lifestyle branding.

Acknowledging inequality It’s heartbreaking and infuriating that police brutality continues to be so prevalent in communities of colour, but it’s inspiring to see the collective will aimed at a just cause and to see change happening legislatively and in more subtle interpersonal ways.

The creative industries will have a huge role to play in this, as they have in all movements. I don’t think it’s my place to say how much progress has been made in the photo industry – my feeling is that those in hiring positions are at least paying more attention to the photographers they hire and in the stories they choose to tell, but that there is always more progress to be made.

The need for risks, that aren’t really risks I would love to see magazines take more risks, and give pages to those who haven’t been given as many opportunities. Most mainstream magazines were already allowing the demands of advertisers to influence content, and now they’re beholden to clicks, likes, and shares. This creates an environment where trend pieces or celebrity profiles push out real storytelling.

With so many of the contributors to magazines being freelance, we need creative directors and editors who are willing to challenge publishers to push their limits. This is also a time for independent magazines to continue to forge their own paths and ignore the expectations of the market.

On the commercial side of things, it’s important for brands to actually engage authentically with their audience by hiring photographers and artists of colour, rather than trying to assume what they want. They will also need to pay a lot more attention to their roles in larger social issues, in terms of climate, income inequality, health, and racial justice, and not solely in their advertising, but in their business practices, as people will continue to hold them accountable.

Collaboration is key in moving forward I love the collaborative nature of the photography industry. There’s a real interconnectedness, where photographers rely on so many others to create a final image. In general, anything that encourages cooperation rather than competition feels like what the world needs at the moment.